The law of diminishing returns catches up to our energy codes. So what’s next?

By James Benya

“Every great cause begins as a movement, becomes a business and eventually degenerates into a racket.”

-Eric Hoffer, The Temper of Our Time

In 1973, a typical classroom or office drew 5 to 6 watts per sq ft for lighting, providing over 1,000 lux. Also, for most commercial applications, lighting was never switched off for appearance and was used for heating the building. And then, virtually overnight, the oil embargo of 1973 started a “movement” to conserve energy in buildings.

Early energy standards, ASHRAE 90.1-1975 and California’s Title 24, forced the staid lighting industry to respond and the seeds of a business in energy efficiency in lighting were planted. At first using readily available technology, the lighting industry seized the business opportunity, and over the next 20 years a regular cycle of inventions and efficient products such as motion sensors, more efficient lamps and electronic ballasts caused ever-decreasing energy code power allowances.

Steering all of this are the ANSI/ASHRAE/IES 90.1, IECC and Title 24 lighting standards. These standards have been adopted by most states as energy codes. Since 2001, these energy codes have been revised every three years, which, in turn, has created code-compliance businesses in simulations, implementation, installation and training, as well the business of updating the codes.

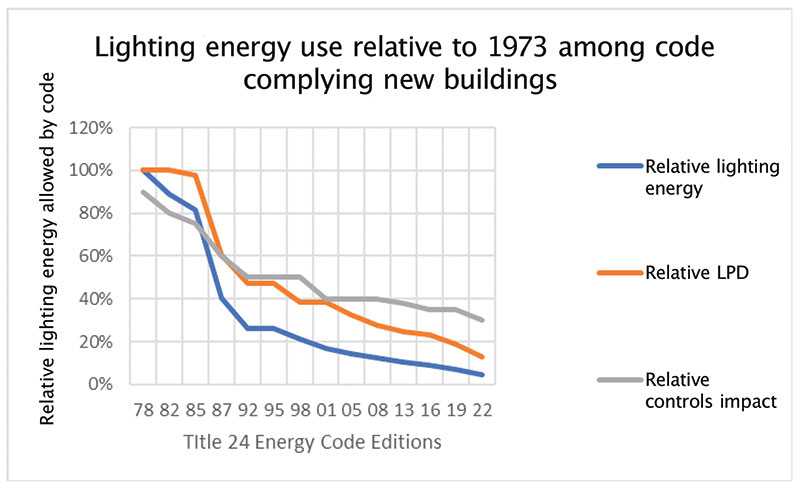

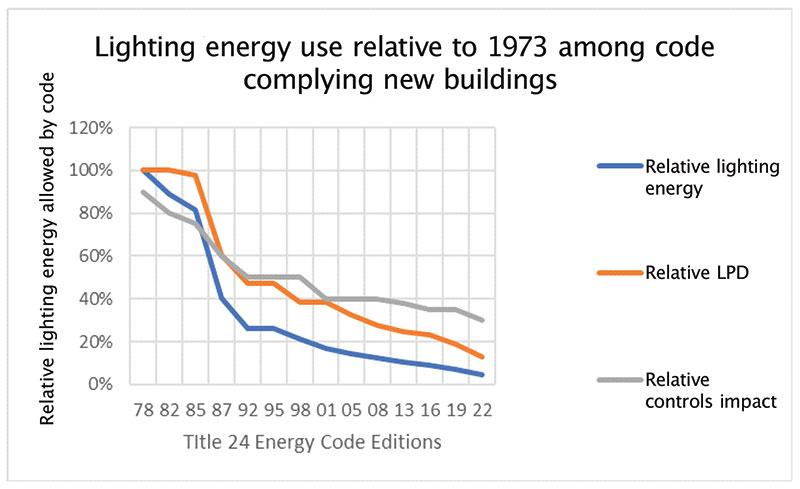

The codes worked well; by 2013, lighting power density (LPD) in new buildings had decreased by 80 percent and operating time had dropped over two-thirds compared to 1973.

GROWTH INDUSTRY

Over time, the business of writing codes has changed dramatically. Once developed by architects, engineers, building officials and members of the utility and manufacturing industry, today’s codes are developed primarily by state and federal agencies like DOE, representatives of manufacturers and industry organizations like NEMA, and consultants in the business of code development, largely supported by industry groups and utilities. Long gone are the people who design, build and inspect buildings. The time commitment and cost for a person to participate in code-writing committees has grown to the point where, by and large, only those supported by corporate funding continue to do the ever-important work of the code committees. Meanwhile, architects, engineers and contractors face the increasing and voluminous documentation required for design and compliance. This has spawned business in code compliance documentation and compliance software. Most recently, justifiably concerned about improper commissioning of lighting controls, California now requires Certified Lighting Controls Acceptance Testing Technicians to confirm the proper operation of lighting controls—another new business opportunity.

In our current decade, the tech sector has finally gotten interested in lighting thanks to LEDs, cost effective controls, wireless communications; more new businesses in lighting were created in the last eight years than all of those that existed in 1973. With these exciting developments, the energy use by lighting will average about 93 percent less by the end of this decade compared to 1973. No other energy savings in the design for buildings comes close.

The fact is we are closing in on the theoretical limit of minimizing lighting power, which, with currently available technologies at their maximum efficiency, is about 97 percent less than 1973. Below is a chart (Figure 1) showing lighting energy use from 1973 to the present based upon the Title 24 for an average of four typical spaces compared to standard practice in 1973. When a curve approaches its theoretical limit, it is called an asymptote, which means it continues to get ever close to the line. We are now already within 7 percent of zero lighting energy use compared to 1973—within five years we will probably be within 3 percent. Lighting energy use in new code-complying buildings is simply going asymptotic towards perfection right now.

COMMON-SENSE CODES

We have reached a point where our reason and approach to lighting energy codes must change. A good code should prevent bad design, embracing evolving emerging technology, but it must also respect good design and reduce the heavy cost of compliance. We need to realize how well we’ve done and stop trying every three years to make the lighting code tighter. We’ve done our job as an industry. We cannot save 100 percent of energy, can we? Let’s stop the triannual race and pay more attention to the need for cost effectiveness. Since we are approaching “perfect,” continuing to try saving the last few percentage points will degenerate the lighting energy code and compliance into a racket.

Instead, rather than continuing to pour enormous resources into new lighting energy codes, we should redirect our brainpower and businesses toward reducing energy use in existing buildings. It’s time to say for new construction the job is done, and work together to make just as big a difference in the existing building stock as quickly as possible.