Redesigning and rebalancing current approaches to lighting

Everyone deserves good lighting, particularly indoors, where many of us spend most of our time. This may be a simple declaration, but in practice, “good lighting” is a challenge to deliver equitably. Thoughtfully designed, high-quality lighting has long been an indicator of wealth and prosperity. In contrast, systemically disadvantaged and vulnerable communities, especially the occupants of public buildings, are often forced to accept substandard lighting.

Light Justice began in 2020 by examining outdoor lighting inequities: how lighting in the public realm has been historically used, both intentionally and inadvertently, to oppress and marginalize communities of color. These instances clearly demonstrate discriminatory social and environmental injustice. Moving indoors, equitable light can be understood as well-designed daylighting and electric lighting that work in concert to provide a positive occupant experience. This light is the appropriate intensity, color and distribution for the facility, prioritizing people who spend the most time in the space. It is attractive; easily controlled to enable useful variability; supports visual acuity and circadian health; designed and specified to be affordable, efficient and sustainable; and an investment in occupant satisfaction, well-being and productivity.

Delivering good lighting sounds straightforward, but this very goal can seem dauntingly complicated, confusing and expensive to most. Overwhelmingly, the lighting industry’s time, talent and technology serve privileged folks who can afford them. Under-resourced communities are especially prone to poor lighting conditions. This is glaringly evident in public facilities—schools, government offices, housing, senior living, healthcare, community centers and incarceration facilities—where workers, students and residents must spend most or all their time. Census records indicate that public facilities are disproportionately occupied by Black, Indigenous and People of Color who are susceptible to the hazards of inadequate building design and systems. This means that vulnerable occupants endure limited or zero access to daylight and views, as well as visually uncomfortable, poorly maintained lighting. Such lighting is often justified as prioritizing affordability, energy efficiency or “security,” but at a direct and ultimately needless cost to quality. The reality is, once you begin to recognize and see “unjust” lighting in the world, you cannot unsee it.

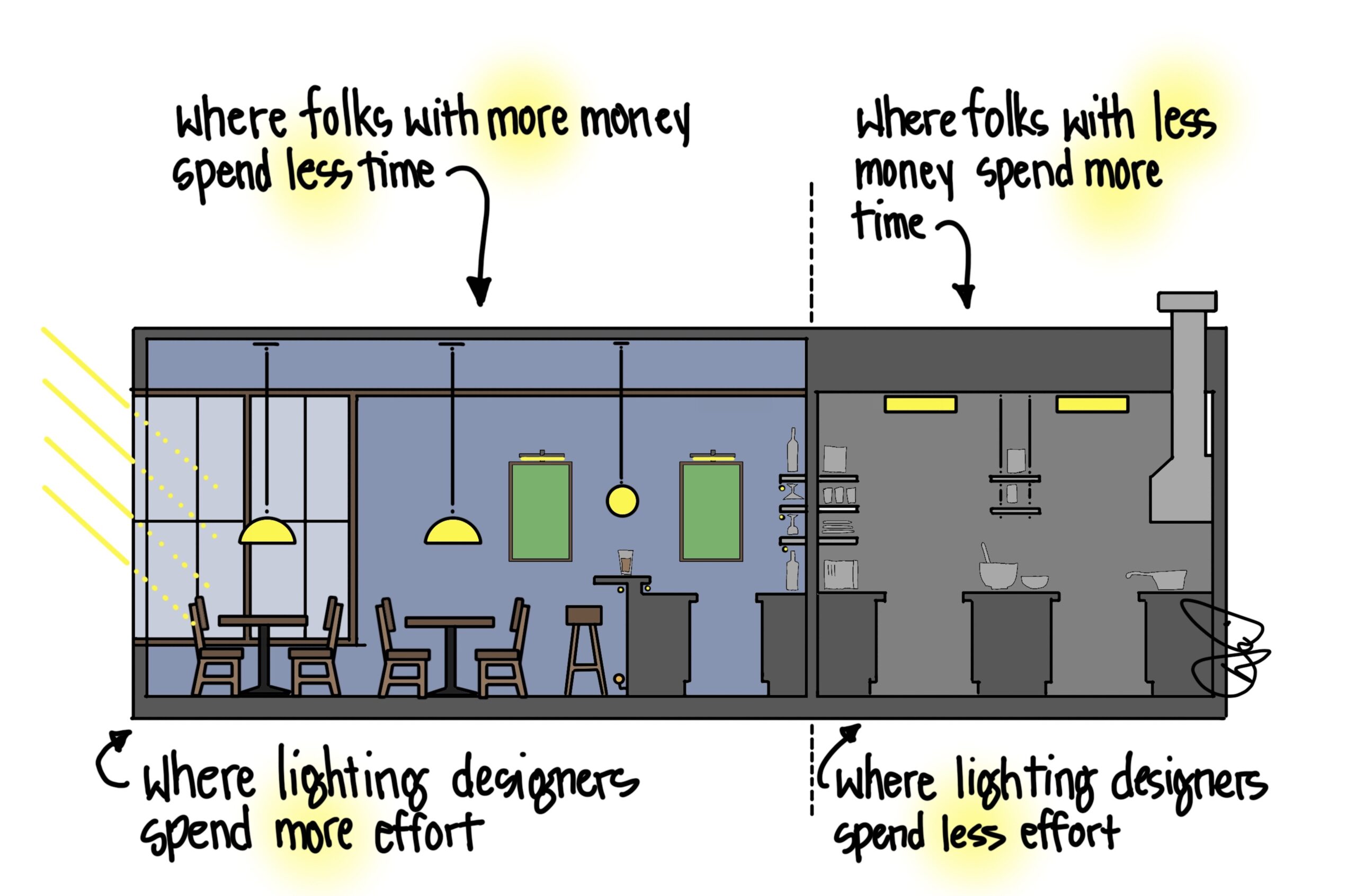

Wealth and class have historically dominated interior design considerations, including access to satisfactory natural and artificial illumination. From the dichotomy of “upstairs/downstairs,” these baked-in assumptions around spatial and lighting privileges have worked their way into “corner office versus cubicle” and “front-of-house versus back-of-house” differentiations. The underlying imbalance, when left unquestioned and unaddressed, remains deeply ingrained in how spaces and their occupants are treated in terms of design attention, material quality, finishes, furnishings and lighting. These inherited and amplified systemic inequities were examined by the Light Justice team in a presentation at LightFair 2023 and subsequently explored by attendee and lighting writer David K. Warfel, who has offered illuminating expository graphics (Figures 1 and 2)(1).

It’s time to focus on forgotten populations. In public facilities, inadequate investment in lighting quality—as well as other aspects of building quality—contributes toward serious long-term, pervasive societal imbalance. Underfunding and lack of design attention can result in distressing and unhealthy lighting conditions, while at the same time, the abruptly accelerated evolution of lighting technology has made modern options less intuitive and understandable to industry outsiders. These poor lighting conditions disproportionately impact the underprivileged, populations who may have, at best, limited agency to improve the lighting that most directly affects their lives.

According to the 2020 Census, 61.6% of the U.S. population identified as “white only,” compared to only 38.4% who identified as non-white(2). The reported student body of K-12 public schools, in contrast, was 54.2% non-white. Many public school teachers and students spend the entire school day with substandard lighting and daylighting due to strained budgets and limited access to design expertise. Classrooms with minimal daylight and no outside view suppress the learning and retention of students who use them(3). Other readily observable examples are post offices, public housing, senior living facilities, community centers and incarceration facilities. The U.S. Postal Service workforce is 49% non-white(4). Non-white renters comprise 59% of public housing occupancy, with 56% of public housing units headed by a person 65 years or older and/or disabled(5). The impact of low-quality lighting in public facilities—a product of neglectful prioritization—is inequitable, unsustainable and inhumane.

The experience of poorly considered, misapplied lighting can be particularly oppressive for those in incarceration facilities, who count among the most powerless in society. “The incarcerated represent a forgotten population, especially within the lighting community,” says Parsons graduate student Richard Muthama in his thesis Equitable Lighting for the Incarcerated. This experience is echoed by Truth, a formally incarcerated person and advocate for reform of the U.S. criminal legal system. Truth recounts, “When I was in the county [prison], you would get a couple of slivers of light in the window depending on where you were…but actual lighting that you get from the light bulb in the cell is super dim. And—this is true for any institution—there’s going to be an officer coming by your cell every hour shining a light in your face, generally in the middle of the night… Sleep deprivation in these spaces is serious. In other institutions, the light in the hall doesn’t shut off, so you have this constant beam of light in the cell all night.”

Lighting in incarceration facilities is typically focused exclusively on security and control. Some institutions deprive prisoners of access to daylight, even in recreational areas. Inhabitants are enclosed in visually distressing environments, which do not support rehabilitation. “It is then necessary, in spaces with limited user autonomy, for designers to provide the best conditions that reflect practices in our everyday spaces,” Muthama advocates. “It is important to create recommendations and guidelines based on normative standards that would provide humane living conditions, comparable to the rest of the built environment.”

Lighting professionals are in the business of delivering good lighting. The fact that accessibility to lighting expertise and high-quality lighting technology has been historically limited for most of society represents an enormous opportunity for the industry. Over the past decade, the overwhelming prioritization of energy efficiency in the name of sustainability resulted in the mandated adoption of LED technology, with those in the general public largely left to fend for themselves in trying to understand and fulfill their own lighting needs. Most people, especially those with limited means, are not equipped with the basic lighting knowledge necessary to make good purchasing decisions. In a provocative and widely read article, “The New Light is Bad”(6), journalist Tom Scocca says, “I checked my nearest Dollar Store and discovered that there were plenty of LED bulbs to be had there. Their color temperature was 6400—the harshest, cheapest possible light, a light so blue that when I Googled it, what came up were grow bulbs. The efficient future of lighting now includes poor people; it just does it by making lighting one more form of privation.” Scocca continues “What we’re starting to glimpse is a new phase in which good light, once easy to achieve and available to everyone, becomes a luxury product or the province of technological obsessives.” The fact is, lighting technology has advanced well beyond the initial goals of improving energy efficiency. The inscrutability and inaccessibility of good lighting is no longer the fault of the industry’s own limits—the greater issue is a gap between those who design lighting and those who are most impacted by it, and this can be bridged. To quote the founder of the Creative Reaction Lab, and leading Design Justice proponent Antionette D. Carroll, “Systems of oppression, injustices and inequities are designed. Therefore, they can be redesigned.”(7)

Our industry has a clear responsibility to inform and educate the general public about not only the value but also the improved accessibility of good lighting. This goes beyond altruism. Such a refocus could extend our reach and impact by serving the whole population, not exclusively those who can afford design consulting and high-end technology. By expanding design and delivery practices in an intentional way, working to overcome historic indoor lighting inequities, lighting professionals also stand to influence and have a greater voice in building design and construction industries. To aim our ambitions in this direction will require us to rethink and reprioritize how we practice lighting design.

The first step is to engage directly with the people who need our expertise. Light Justice is inspired by Design Justice, an approach to design which involves users and occupants as equal partners in the design process(8). In the context of Light Justice, “good lighting” must be truly occupant empowered and empowering. Ideally, the lighting design for a space emerges from direct engagement with occupants to understand their visual preferences and apprehensions, incorporates this information in communication with and calibration of underlying design goals, then responds with well-designed, affordable, controllable and maintainable lighting systems. Instead of acting as a “Lighting Authority,” we need to interact and empathize with the building users and occupants, and work to enable them to inform and understand design decisions.

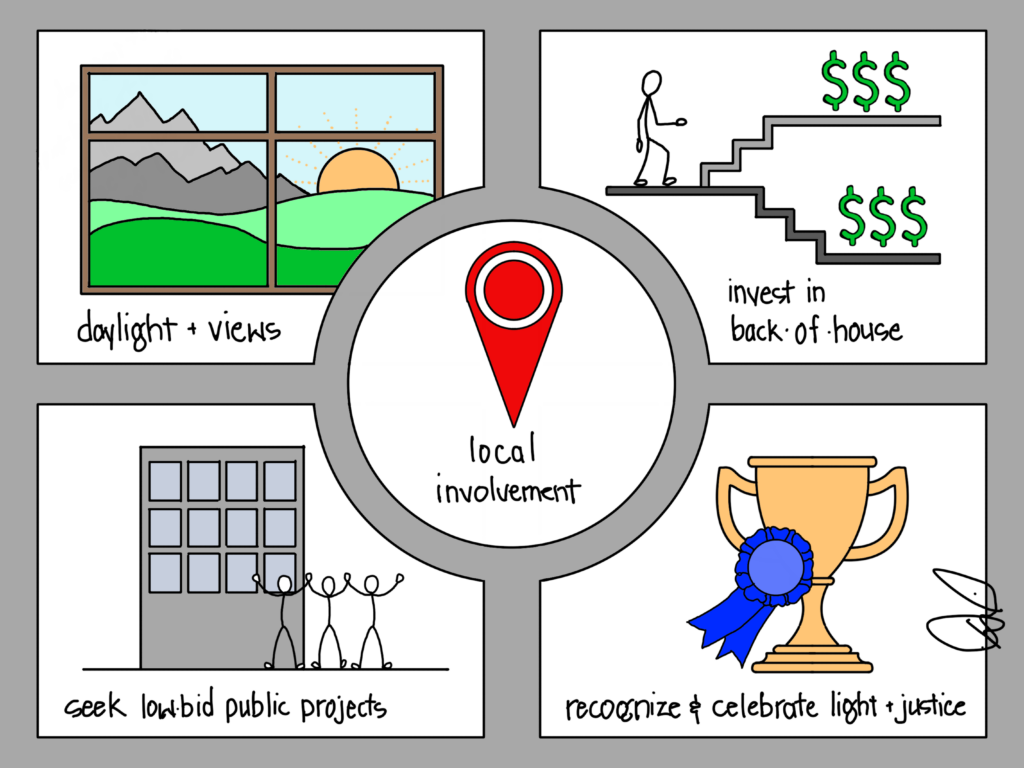

Along with undertaking a more inclusive design process, there are concrete ways to practice equitable lighting.

- Prioritize daylight and views: Before the 1920s, daylight was the primary source of daytime illumination in schools and public buildings. By the 1960s, after the widespread use of air conditioning and fluorescent lighting, it became a neglected resource in buildings, no longer designed to optimize natural light and ventilation. We have since learned that daylight in buildings is a desirable amenity measurably beneficial to human health, satisfaction and productivity. Daylight makes buildings more environmentally sustainable. It increases building value and economic performance as demonstrated by LEED, WELL and Living Building programs.

- Invest in “back-of-house” spaces: Workers spend much of their time in back-of-house spaces, which are frequently dismal areas occupying the least desirable part of a building. Workrooms and breakrooms without daylight are commonly illuminated with utilitarian, outdated luminaires. Usually, lighting designers are asked to prioritize the “specialty” and “hospitality” areas in buildings. Back-of-house has become synonymous with minimal attention, with a glance at codes and standards at best. This paradigm is overdue for flipping. Lighting designers can, particularly with vocal industry and manufacturer support and concerted client education, ensure that back-of-house occupants benefit from the same meaningful lighting standards and quality definitions as “front-of-house” visitors—eliminating glare and flicker, providing intuitive controls and adding daylight, while considering affordability and maintainability.

- Seek “low-bid” projects: As an industry, we tend to shy away from publicly funded projects due to concerns that these projects will be lengthy, low-budget, design-constrained and unprofitable. The design standards for publicly-funded buildings often lag behind the expectations for commercial buildings. However, lighting professionals are best able to both deliver pleasing outcomes within cost and energy limits as well as defend design proposals against aggressive value engineering. Good lighting is a valuable investment in public health and broader prosperity for everyone, and low-bid projects have an outsized impact on quality of life and human experience for the resources they consume.

- Recognize excellence in equitable lighting: Lighting awards have traditionally gone to well-funded and beautifully photographed projects. The IALD, IES and other lighting organizations could add award categories for lighting projects that serve and benefit historically under-resourced, neglected or marginalized communities through an equitable design process of community engagement and collaboration. This means of recognition would have the effect of encouraging lighting studios around the world to work on more equitable design as well as energizing emerging designers to actively seek out smaller local projects with limited budgets. Such an incentivization could also promote increasing instances of creative cross-collaboration, encouraging lighting manufacturers and distributors to support the practice of Light Justice, both indoors and outdoors.

Of course, “good lighting” is only one of many critical factors that will compose a more holistic, lasting solution that gets to the root of social and environmental inequities. The reality is that as an industry, we have special knowledge that must be shared to benefit the human condition on a larger scale. Our professional responsibility is to bridge the knowledge gap between lighting experts and lighting consumers—particularly those with limited resources. At a policy level, we must advocate for design standards requiring lighting which improves quality of life for all, without adding to the historic neglect of the vulnerable: workers and children, as well as the elderly, disabled, neurodiverse and incarcerated. On a practice level, we can work toward a greater openness to engaging with communities and occupants. At a personal level, we must consider how our practice serves more than the wealthy, privileged and powerful. As an industry, we can redesign and rebalance our approach to lighting for humanity—and it is time for us to undertake this effort together.

THE AUTHORS|

Edward Bartholomew, Mark Loeffler and Lya Shaffer Osborn are lighting designers and the founding curators of Light Justice (https://lightjustice. org), a knowledge exchange forum addressing the need for equitable lighting to serve social and environmental justice. Light Justice believes that everyone deserves good lighting, especially marginalized and vulnerable communities.

References

(1) “Lighting Hope for All of Us” by David K. Warfel, Designing Lighting, June 2023. Available: https://issuu.com/designinglighting/docs/dl_june_2023/s/28187742

(2) “Race and Ethnicity in the United States” by the US Census Bureau , 2020. Available: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html

(3) “A Literature Review of the Effects of Natural Light on Building Occupants” by L. Edwards and P. Torcellini, National Renewable Energy Lab, July 2022. Available: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy02osti/30769.pdf

(4) “Diversity in the US Postal Service” by AUSPL. Available: https://auspl.com/diversity-in-the-us-postal-service/

(5) “Policy Basics: Public Housing” by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities; June 21, 2021. Available: https://www.cbpp.org/research/public-housing

(6) “The New Light is Bad” by Tom Scocca; New York Magazine, March 30, 2023. Available: https://nymag.com/strategist/article/led-light-bulbs-investigation.html

(7) Creative Reaction Lab. Available: https://crxlab.org/

(8) Design Justice Network Principles. Available: https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles